Is Art For Everyone?

Is Art For Everyone?

While it’s true that not everyone feels naturally drawn to art, it’s important to remember that art itself is never meant to be exclusive. At its core, it exists for everyone, to be seen, questioned, interpreted, or simply enjoyed in whatever way resonates. Engaging with creative expression, whether through viewing or making, is not just a matter of taste but of well-being. The act of consuming and creating art nurtures a healthier relationship with ourselves and the world around us, strengthening neuroplasticity, fostering empathy, and keeping our minds open to new ways of seeing and thinking.

Art, they say, is for everyone. But if you’ve been inside the machinery long enough, you know that isn’t quite true. Not everyone feels it. Not everyone even has the wiring for it. That doesn’t mean art is exclusive, it just means the doorway is narrower than we like to admit.

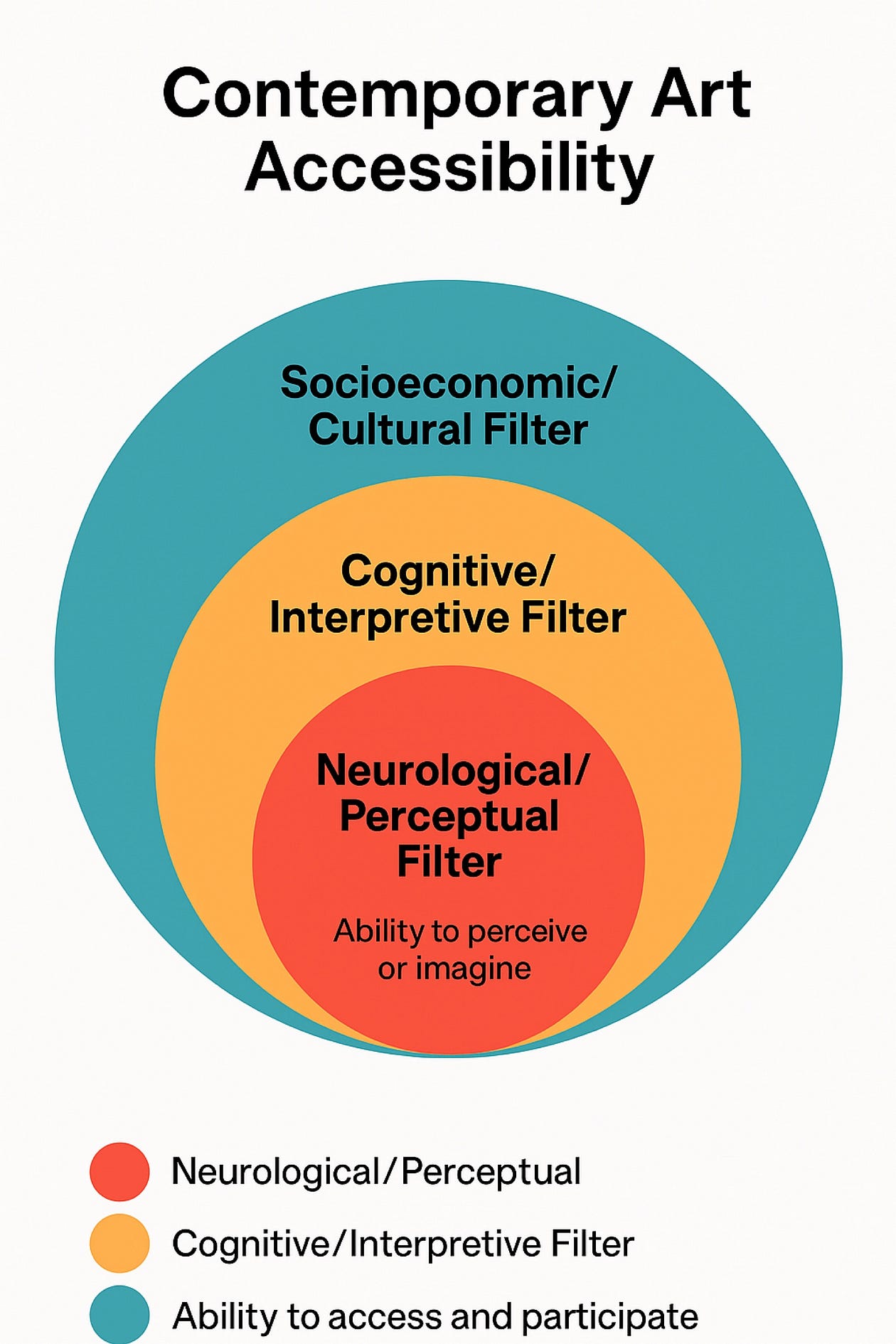

I’ve started to think about this in circles, three filters that decide who can really step inside.

The First Circle: Neurology

At the very center is the body’s own architecture.

• Aphantasia — the inability to form mental images — affects roughly 2 — 5% of people worldwide (Zeman et al., University of Exeter, 2015). For them, “imagine a red apple” results in a blank mind’s eye. No images. This makes works that rely on visualization or imaginative projection far less accessible.

• Likewise, inner monologue is not universal. Some studies suggest that 5 — 10% of people rarely or never experience inner speech (Hurlburt & Heavey, 2015). For such individuals, the symbolic or narrative dimensions of art, what a painting “says,” may not register in the same way.

Creativity has long been mistaken as a gift bestowed upon a rare few, when in truth it reflects the way our brains balance imagination with structure. Neuroscience shows that creative individuals often maintain a more fluid connection between the brain’s default mode network, the realm of daydreaming and free association, and the executive control network, which organizes and refines thought. This interplay allows for the generation of novel ideas that can be sculpted into form. By contrast, those who identify as “non-creative” often lean more heavily on rigid filters or reward systems that favor correctness over exploration. It’s not that their minds are deficient, but that their neurological wiring favors convergence and certainty rather than divergence and experimentation.

On a cognitive level, this difference often plays out as a comfort or discomfort with ambiguity. The creative process is inherently open-ended, rarely offering a single right answer. To thrive in it requires a tolerance for uncertainty, a willingness to hold onto multiple possibilities before resolving them. Creative thinkers tend to let their working memory operate more loosely, allowing unrelated fragments of thought to slip in and recombine in surprising ways. Those who feel less inclined toward creativity often filter too much too soon, collapsing the unknown into the known before new connections have a chance to spark. This preference for order over possibility can feel like an inhibition, especially in artistic contexts where freedom of interpretation is the very point.

Just as powerful as these neurological and cognitive tendencies, however, are the psychological and cultural habits we inherit. Many people have been conditioned out of creativity through education that prizes efficiency, correctness, and external validation. Fear of failure or judgment then cements the habit of avoidance: better not to make art at all than risk making “bad” art. Yet this inhibition is not a permanent barrier but a learned reflex. Creativity is not exclusive, it is a birthright of our species, a skill honed by curiosity and play as much as by training. The difference between those who participate in artistic action and those who do not often has less to do with innate ability than with the willingness to enter uncertainty and trust that something meaningful can be found there.

These neurological variations aren’t deficiencies, but they change how people receive. An abstract painting may feel hollow, not because they lack curiosity, but because their cognitive hardware doesn’t play along.

So at this innermost level, a percentage of humanity is excluded from the kind of imaginative engagement most contemporary art assumes as a baseline.

The Second Circle: Interpretation

Creative literacy and engagement, the kind no school teaches properly.

• Global self-perception of creativity is surprisingly low. Adobe’s State of Create report (2012) found that only 39% of people worldwide considered themselves creative, while in the U.S. the number was just over 50%. A YouGov survey (2023) similarly found 49% of Americans consider themselves “artistic.” In other words, about half of the population opts out of identifying with imagination at all.

• Museum studies reinforce this: visitors frequently report feeling “intimidated” or “underprepared” when viewing modern and contemporary art (Falk & Dierking, The Museum Experience Revisited, 2013). Lack of confidence in one’s interpretive ability often leads to disengagement.

The result: without training in visual literacy, symbolic language, or historical context, much of contemporary art appears as decoration or confusion. The gallery visit becomes a shrug.

John Akomfrah, reflecting on his absence in canonical museum spaces:

“If you wander around the Tate Gallery for years and years… at some point it’s going to dawn on you: I’m not here. There is no representation of people like me.”

Bernice Bing, via essayist Jordan Wiebe, on art-world fence-building:

“The art world deploys subtle and overt gatekeeping, deciding whose creativity fills gallery walls and whose remains hidden in closets.”

Interpretation, like language, must be learned. And when it isn’t, the work is invisible, even when you’re standing right in front of it.

The Third Circle: Economy

Finally, the outermost ring: money, atmosphere, the velvet rope of the art world.

• The global art market was valued at $65 billion in 2023 (Art Basel & UBS report). That market is driven disproportionately by the ultra-wealthy: just 1% of collectors account for nearly two-thirds of total sales.

• Museum admissions create another filter. In the U.S., fewer than 24% of adults report visiting an art museum in the past year (National Endowment for the Arts, 2017 survey). Barriers include cost, geography, and cultural perception (“that space isn’t for me”).

Meanwhile, collectors, those with consistent access, often do not see themselves as creative. Anecdotally, many frame their role as custodians of value, not participants in imagination. This paradox underscores how the outer circle functions: ownership and access are social, not always aesthetic.

Ibiyinka Alao, pointing to institutional elitism:

“Many big art institutions, especially in the Western world are yet to come to terms with a way of showing art without making it appeal only to the elite, thereby losing its true meaning.”

Sarah M. Berry, working with marginalized communities:

“It is my goal for participants to learn that art belongs to them no matter what messages they’ve received that say otherwise… Art belongs to all of them.”

Thus, the outer ring of access reinforces exclusivity, regardless of one’s neurological or interpretive capacities.

The Narrow Eye of the Needle

When all three circles overlap, neurological capacity, interpretive literacy, and financial access; you arrive at the small group of people the contemporary art world truly speaks to.

This explains why the field can feel like an echo chamber: artists talking to artists, collectors circling around collectors, curators shuffling names in a small orbit. The world outside, the half of humanity that doesn’t call itself creative, the many without images in their heads, the millions for whom museums are alien spaces, is left behind.

Shirin Neshat, on art’s primal power:

“I think works of art… have the capability to give people a certain hope and passion and belief and conviction that nothing else can. I think there is something about creativity and the imagination that is ultimately very primal…”

Art doesn’t need to be universal to be vital. Mystery has always lived in the few. But honesty about these filters might allow us to create new doors, entry points that bypass the usual checkpoints of neurology, interpretation, and wealth.

From the earliest marks etched onto cave walls to the digital canvases of our present age, creativity has been one of humanity’s most vital instruments of survival and progress. It is not a luxury, nor a mere ornament of culture, it has been central to our growth. Creativity allowed our ancestors to imagine tools before they existed, to tell stories that bound communities together, and to envision possibilities beyond immediate necessity. As societies grew more complex, creativity guided not only our art but our sciences, our technologies, and our systems of belief. It has consistently stood at the forefront of human thought, enabling us to endure hardship, to adapt to changing environments, and to thrive in ways no other species has. In every successful society, creativity has been both a mirror of its people and a lantern carried forward, illuminating paths toward resilience, innovation, and shared meaning. To neglect creativity, then, is not simply to disregard art, it is to forget the very faculty that has carried us through millennia of uncertainty into the civilizations we call home today.

Even those who don’t call themselves creative still want wonder. They may not crave the painting itself, but they crave the pause, the beauty, the brush with mystery. That, I believe, is art’s enduring promise, to encourage us to question and interpret everything.

Art, Photos, and Writing by Harrison Love

Harrison Love is Artist and Author of “The Hidden Way,” an award winning illustrated novel inspired by first hand interviews about Amazonian stories. He is also the Founder of the Permaculture Art Gallery STOA. More information about his Art and Writing can be found on www.harrisonlove.com

Footnotes / References

1. Aphantasia prevalence: Zeman, A., Dewar, M., & Della Sala, S. (2015). Lives without imagery — Congenital aphantasia. Cortex, 73, 378 — 380.

— First scientific description of congenital aphantasia, estimating ~2 — 5% prevalence.

2. Inner monologue variation: Hurlburt, R. T., & Heavey, C. L. (2015). Investigating inner experience: The descriptive experience sampling method. Cambridge University Press.

— Studies show inner speech varies widely, with 5 — 10% reporting little or none.

3. Global creativity self-perception: Adobe. (2012). State of Create: Global Benchmark Study.

— Found only 39% of respondents worldwide identified as creative; >50% in U.S.

4. U.S. artistic self-identification: YouGov. (2023). How artistic are Americans? Retrieved from today.yougov.com.

— Survey found 49% of Americans consider themselves “artistic.”

5. Museum visitor intimidation: Falk, J. H., & Dierking, L. D. (2013). The Museum Experience Revisited. Routledge.

— Visitor studies show many report feeling underprepared or intimidated in contemporary art settings.

6. Global art market size: Art Basel & UBS. (2024). The Art Market 2024: An Art Basel & UBS Report.

— Valued the global art market at $65 billion in 2023.

7. Collector concentration: McAndrew, C. (2024). The Art Market 2024 Report.

— Data showing the top 1% of collectors account for nearly two-thirds of sales.

8. U.S. museum attendance: National Endowment for the Arts (2017). U.S. Patterns of Arts Participation: 2017 Survey of Public Participation in the Arts.

— Found 24% of adults visited an art museum in the past year.

Comments

Post a Comment