Art Escapes Control

Art Escapes Control

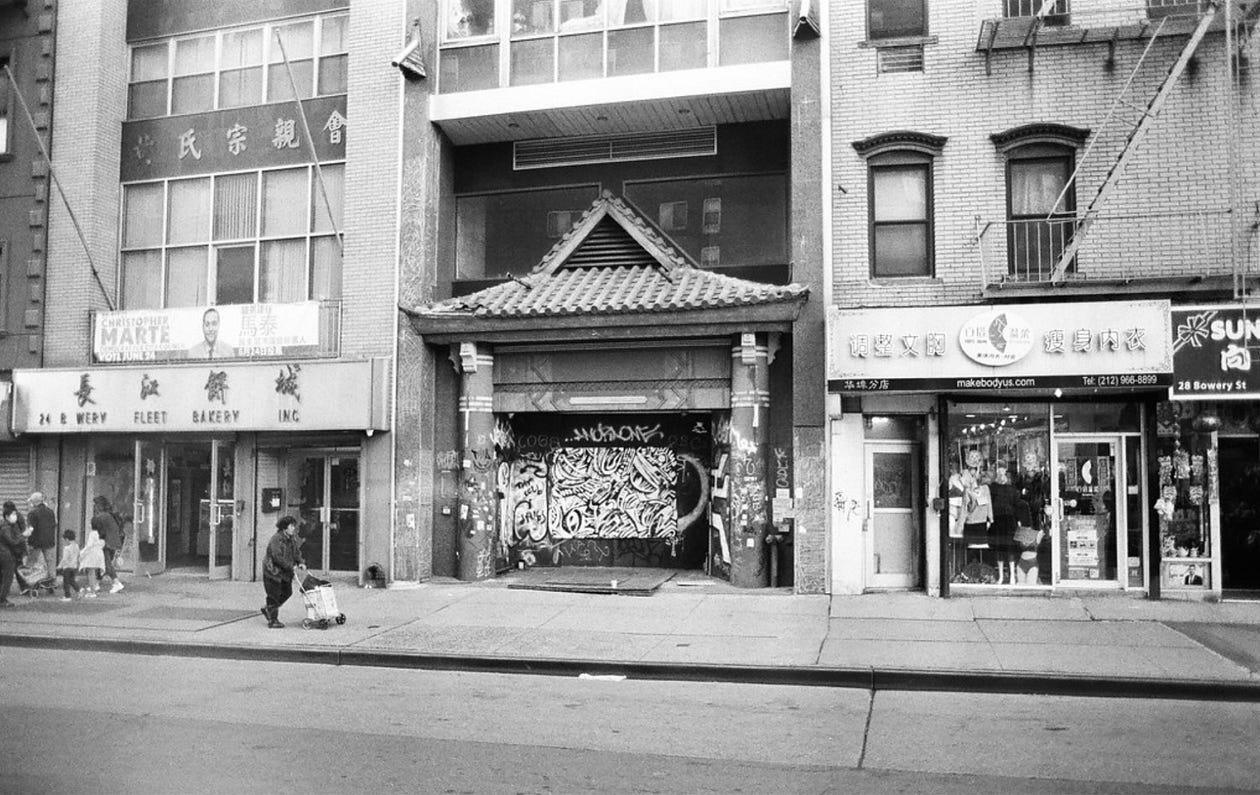

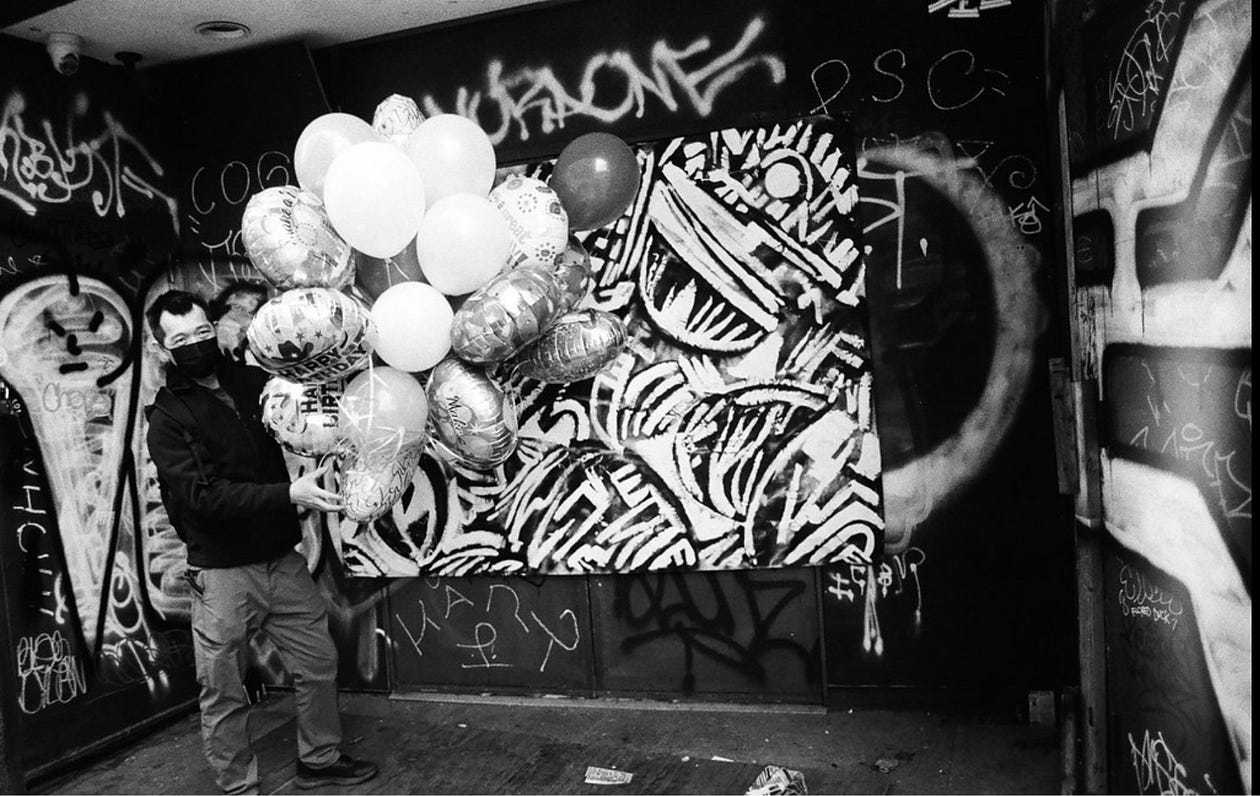

This past summer, I began a project documenting the placement of my paintings into the streets of Soho, a neighborhood long associated with the shifting tides of contemporary art. Each month, I installed large paintings on disposable tarps a spot near Chinatown, a site that had been shuttered for fifteen years. Instead of pristine canvases inside white-walled galleries, these works were suspended in a state of vulnerability: exposed to vandalism, theft, and the gaze of passersby who never asked to encounter them.

“Even the most perfect reproduction of a work of art is lacking in one element: its presence in time and space, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be.”- Walter Benjamin, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.

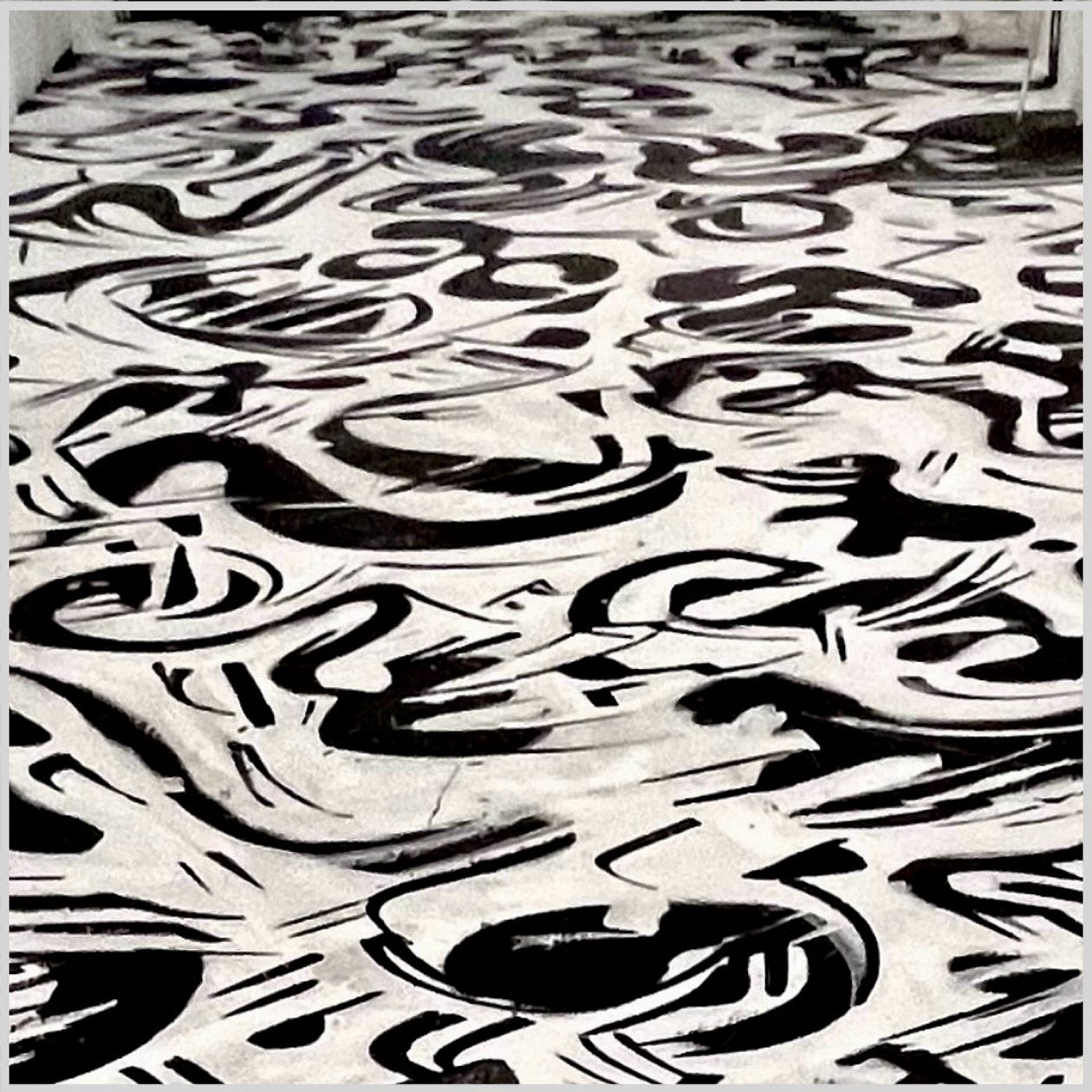

What interested me was not permanence but process, not preservation, but the possibility of transformation once art leaves the studio and enters the public domain. The gallery, for all its prestige, can function as a greenhouse: it incubates and protects artworks, but also contains them. By contrast, releasing art into the streets is more akin to returning an animal to its natural environment, a wild action. The artwork is no longer a static object but a participant in a living system, interacting with people, architecture, and chance.

From a psychological perspective, this taps into our collective fascination with impermanence and unpredictability. Freud described art as a sublimation of human instincts, a way to negotiate between desire and societal rules. By giving art to the street, I was releasing that sublimation back into its raw state, art unmediated by price tags, collector’s expectations, or the silent etiquette of gallery spaces. The public becomes not just the audience but also the co-creator, shaping the fate of the work through acts of vandalism, theft, or reinterpretation.

In this way, the project was an experiment in freedom: art that could not be fully owned or contained, art that refused domestication. It was an attempt to rewild inspiration, to see what happens when beauty, like nature, is allowed to run untamed.

The City as a Stage, the City as a Consumer

The setting of this project was not chosen for nostalgia or symbolism alone, but for the vitality of the urban environment itself. In New York, no surface remains neutral; every wall, doorway, or abandoned façade is part of an endless palimpsest. Posters are layered until they become accidental collages, graffiti is buffed and reapplied in a perpetual cycle, and construction scaffolding becomes a temporary gallery of marks. By entering this space, my paintings became part of the city’s metabolism; absorbed, digested, and eventually transformed.

Urban theorists like Henri Lefebvre argued that the city is not just a backdrop but a “produced space,” a living, dynamic entity created through human activity. To place artwork into such a space is to acknowledge that it will inevitably be shaped by forces beyond the artist’s control. The city itself becomes a co-author: the grime of the street, the curiosity of strangers, and the acts of vandalism or theft are not interruptions but continuations of the work.

“The city is a practiced place. It is a space that is lived in through walking, consuming, and inhabiting, a canvas for daily action.”- Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life

This consumption of art by the city mirrors psychological processes as well. Just as an individual psyche integrates or resists new experiences, the city integrates or resists artistic interventions. Carl Jung described the unconscious as a vast landscape where archetypes emerge and disappear, constantly reshaped by lived experience. In this sense, the city can be understood as a collective unconscious in concrete form — an immense psychological canvas where art is projected, reinterpreted, and sometimes obliterated.

The fate of each painting whether vandalized, stolen, or relocated is proof of the city’s appetite. The works were not static displays but offerings cast into the urban current, subject to the desires and aggressions of anonymous hands. This is not unlike ritual sacrifice: once released, the work no longer belongs to the maker but to the forces that claim it. In this way, the city consumes art just as it consumes everything placed within it, folding it into its ongoing story.

The Life Cycle of the Work: Vandalism, Theft, Relocation

Each month brought a new fate for the paintings: vandalism, theft, theft again, and finally, relocation. To the casual observer, these might appear as interruptions, failures, or losses. But to me, they felt like the real experiment; the artworks had been absorbed into the city’s metabolism and were living second lives outside of my control.

In the gallery system, artworks are protected from entropy. They are conserved, climate-controlled, and insured. The artist’s intent is preserved as an object of cultural capital. Yet theorists from Walter Benjamin to Nicolas Bourriaud have argued that art does not truly live until it interacts with an audience. Benjamin’s idea of the aura, the singular presence of a work in time and space, takes on a new intensity when that aura is threatened by disappearance or mutation. A stolen tarp painting may have “lost” its aura as an intact work, but it gained another, more elusive one: the aura of risk, encounter, and urban myth.

“The creative act is not performed by the artist alone; the spectator brings the work in contact with the external world, completing its meaning.”- Marcel Duchamp, Art and the Object

In a way, the vandal who scrawled on my first piece was collaborating with me. Their marks, however destructive, extended the work beyond its original design. The thieves who carried off later paintings became co-authors too. Duchamp argued that the viewer completes the artwork through interpretation, but here the public went further: they completed it through action. Their interventions underscored what Roland Barthes described as the “death of the author,” the moment when meaning escapes the artist’s hand and becomes fully open to the world’s interpretations.

I found myself welcoming this openness. When a work was stolen, I took it as a great compliment. It meant that someone desired it enough to act, to risk taking it, to burden themselves with its size and weight, to claim it as their own. Perhaps it was hung in a private space, or resold, or maybe it was cut up and sewn into clothing. The thought amused me: that my paintings might circulate not only on walls but on bodies, becoming mobile artifacts of the city.

“By making art public, by detaching it from the aura of tradition, we allow it to function in the sphere of reception and reinterpretation.”- Walter Benjamin

This cycle of loss and transformation aligns with systems theory in art, which treats artworks as dynamic nodes within broader environments. Much like ecological systems, public art thrives on disturbance: vandalism, theft, and displacement are not interruptions but forms of feedback. They prevent the work from becoming static, keeping it in flux. From this perspective, the city itself was the true medium, and my tarps were simply catalysts within it.

What emerged was a new understanding of artistic authorship: one not rooted in control, but in release. The life cycle of these paintings demonstrated that art, when set free, does not die, it multiplies.

Gifting vs. Commodification

This project was also, in many ways, a personal statement against the malfunctioning gallery model. For decades, the gallery has served as the central node of legitimacy in the art world, a system that not only frames and protects art but also commodifies it. Yet in recent years, that system has faltered, fewer galleries, fewer buyers, and a narrowing of opportunity as art becomes increasingly subject to speculation rather than engagement.

By placing paintings on tarps into the streets, I was creating a counter-gesture: art not as a commodity but as a gift. This recalls the anthropologist Marcel Mauss’s classic essay The Gift, in which he describes how the exchange of gifts in traditional societies establishes bonds of reciprocity and community. Unlike commodities, which circulate through impersonal markets, gifts create relationships. Once something is given, it carries a part of the giver, obliging the receiver to respond in some way, even if that response is anonymous vandalism or theft.

“The gift is never free; it creates obligations, bonds, and relations that circulate value in ways that exceed mere calculation.”- Marcel Mauss, The Gift.

The cultural critic Lewis Hyde took this further in The Gift: Imagination and the Erotic Life of Property, arguing that art itself is best understood as part of the gift economy. “The gift must always move,” Hyde writes; it loses vitality when it is hoarded or frozen in place. A painting locked away in a storage facility may increase in market value, but it ceases to live. By contrast, a painting stolen from the street, cut into fragments, and remade into a garment may be worthless to an auction house but invaluable as a continuation of creativity.

“A work of art is not fully alive until it moves; it loses its vitality when hoarded or commodified.”- Lewis Hyde, The Gift

This tension between the gift and the commodity maps onto psychology as well. Commodification is about control, possession, and scarcity , the ego’s attempt to fix value. Gifting is about openness, vulnerability, and abundance, a recognition that meaning expands when it is shared. By gifting art to the city, I was nourishing it in a way that the market cannot: freely, without expectation of return, and with the understanding that the “return” might come in unpredictable forms, whether vandalism, relocation, or memory.

In this sense, the project was not simply about public art but about reconfiguring value itself. What is more valuable: a canvas protected in a collector’s loft, or a tarp painting claimed by a stranger and carried into the unknown? The malfunctioning gallery model, increasingly cut off from the wider public, has reduced art to a token of wealth. My project sought to break that cycle, returning art to circulation as a living gift, and to let the city itself become the gallery.

The Wildness of Art: Rewilding Inspiration

The word rewilding is typically applied to ecology, the process of restoring ecosystems to their untamed state by reintroducing species, removing barriers, and allowing natural processes to unfold. Wolves returned to Yellowstone, rivers freed from dams, forests left to regenerate. In each case, the wild is not chaos but balance. It is a dynamic system richer and more resilient than any controlled environment.

“Creativity takes courage, and it flourishes only when it is not restrained by expectation or convention.”- Henri Matisse (on painting and instinct)

I began to think of art in similar terms. The gallery functions as a kind of zoo: a carefully maintained enclosure where works can be viewed safely, curated, and preserved. But once art is confined too long, it risks losing its vitality. By releasing paintings into the street, I was engaging in an act of cultural rewilding, reintroducing art into its natural ecosystem: the unpredictable currents of the city.

Graffiti and street art have long embodied this wildness. Emerging as acts of defiance, they reject domestication by institutions. A spray-painted tag, a wheat-pasted poster, or a mural across a brick wall exists in tension with its environment, vulnerable, temporary, and often destined to be erased. Yet this very vulnerability gives it life. Like a wildflower pushing through concrete, it insists on presence despite odds. In this sense, my tarp paintings were less a break from tradition than a continuation of this lineage: ephemeral gestures that thrive precisely because they can disappear.

From a psychological perspective, rewilding art also means tapping into what Jung described as the archetype of the Trickster, the disruptive force that unsettles order to restore vitality. Tricksters steal fire, redraw boundaries, and expose hypocrisy. When my paintings were stolen or vandalized, they were not being destroyed but transformed through this archetypal energy. The Trickster had taken them, ensuring they did not remain static but entered into new, unknown forms of life.

Rewilding also speaks to the unconscious. Freud saw art as sublimation, a taming of instinct into cultural form. But the unconscious resists total domestication; it leaks, erupts, insists on expression. Street art and by extension, my project can be seen as art’s return to instinct, art refusing to be sublimated entirely, a reminder that creativity has roots deeper than the market or the museum.

In this way, rewilding inspiration is both an ecological and cultural necessity. Just as ecosystems need predators, decay, and disturbance to thrive, so too does art need unpredictability, risk, and disappearance. To rewild art is to allow it to escape our control, to let it be carried off by strangers, to invite vandalism, to accept impermanence. It is to recognize that art is most alive not when it is conserved, but when it runs free.

Public Space as a Canvas

To place a painting in the street is to engage in a centuries-old tradition: treating public space as a canvas. From Paleolithic cave walls to the murals of ancient Rome, from Mexican muralism to the graffiti movements of the late twentieth century, artists have always sought to inscribe collective life into shared surfaces. Public art is not an afterthought to culture but its foundation.

By installing tarp paintings in the streets of Soho, I was entering into this lineage, though with a crucial distinction. These were not sanctioned murals commissioned by institutions, nor illegal graffiti acts made under cover of night. They were something in between: legal, temporary gifts placed in a liminal zone of visibility, exposed to the same vulnerabilities as wheat-pasted posters. In this way, the project blurred categories: fine art, street art, intervention. It was not so much a mural as a gesture of occupation, a way of saying: this space can hold beauty, even if only for a moment.

The politics of public space make this gesture significant. Philosopher Hannah Arendt argued that the polis — the shared space of appearance, is where freedom becomes visible. When art enters this arena, it ceases to be private expression and becomes part of the civic dialogue. It can be embraced, defaced, ignored, or claimed, but it cannot be sealed off. To bring art into public space is to submit it to democracy in its rawest form.

This act also democratizes access. The gallery and museum model requires thresholds: admission fees, social codes, geographic privilege. The street, by contrast, offers no barriers. Anyone, a child, a passerby, a worker on break, can encounter the work without preparation. The audience is not self-selecting but accidental. As Michel de Certeau suggested, the city is defined by its “practices of everyday life,” and public art intervenes directly in those practices, catching people unawares and altering their daily trajectories.

There is also a poetics of material. By working on tarps once used for concert posters, I was literally inscribing paintings onto recycled fragments of the city’s commercial language. These surfaces had already lived other lives, broadcasting entertainment and commerce before being repurposed into carriers of abstract mark-making. In this way, the project echoed the palimpsest quality of urban walls: surfaces written, erased, and rewritten endlessly.

“Everyday practices of the city are performances; to intervene in them is to alter the rhythm of public life.”- Michel de Certeau

Ultimately, treating public space as a canvas is less about permanence than about participation. The work enters the flux of the city, exposed to all its dangers and possibilities. It may vanish within hours or linger for weeks, but during that time, it transforms the everyday environment into an aesthetic encounter. Public space becomes not only a backdrop to art, but the art itself.

Wild Art

The Soho project was an experiment in letting go. Across four months, the paintings were vandalized, stolen, relocated and in each case, they became something more than the objects I had created. They were absorbed into the rhythms of the city, participating in a dialogue I could not fully witness or direct. In this sense, the work was truly alive only once it had escaped my control.

Art, like life, gains vitality when it is unpredictable. The thefts and interventions, far from being failures, were confirmations that the project had succeeded in its aim: to return creativity to the streets and to the public, and to see how the city itself would shape it. By gifting work to urban space, I explored the tension between possession and experience, between commodity and gift, and between artist and audience. Each act of displacement, each act of appropriation, became a continuation of the painting’s story.

Philosophically, this project reflects a paradox at the heart of contemporary art. We live in a world where artworks are often valued for their market potential rather than their capacity to provoke thought or nourish community. By placing paintings in public, I was testing an alternative model, one rooted in freedom, interaction, and impermanence. In doing so, I engaged with ecological, psychological, and cultural principles: the rewilding of inspiration, the Trickster energy of unpredictability, the city as a collective unconscious, and the gift as a vehicle for connection.

Ultimately, the work asks a simple question: what happens when art is not controlled, not commodified, not conserved? The answer is evident in the life of these paintings: they multiply, travel, transform, and persist in ways that defy ownership. Their journey affirms a principle that any artist must recognize: the moment art leaves the studio, it belongs to the world, and in that belonging, it finds a freedom no gallery can ever provide.

“The vitality of art depends upon its circulation, upon its capacity to move from hand to hand and transform along the way.”- Lewis Hyde, The Gift

Art that escapes control is art that truly lives, ephemeral, untamed, and endlessly generative. It is, in every sense, the wild heart of creativity itself.

Photos, Art and Writing by Harrison Love

Harrison Love is Artist and Author of “The Hidden Way,” an award winning illustrated novel inspired by first hand interviews about Amazonian Myths and Folklore. He is also the Founder of the Permaculture Art Gallery STOA. More information about his Art and Writing can be found on www.harrisonlove.com

Comments

Post a Comment